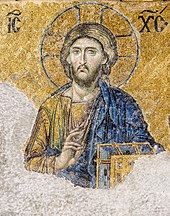

Medieval Art Showing Jesus Classical Art Taht Is More Perfect Than Real Life

Christian art is sacred fine art which uses themes and imagery from Christianity. Most Christian groups use or have used fine art to some extent, including early on Christian art and architecture and Christian media.

Images of Jesus and narrative scenes from the Life of Christ are the most mutual subjects, and scenes from the Old Attestation play a office in the art of near denominations. Images of the Virgin Mary and saints are much rarer in Protestant art than that of Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.

Christianity makes far wider use of images than related religions, in which figurative representations are forbidden, such as Islam and Judaism. However, there are some that accept promoted aniconism in Christianity, and there have been periods of iconoclasm within Christianity, though this is non an common interpretation of Christian theology.[1]

History [edit]

Beginnings [edit]

Virgin and Child. Wall painting from the early catacombs, Rome, 4th century.

Early Christian art survives from dates near the origins of Christianity. The oldest Christian sculptures are from sarcophagi, dating to the showtime of the 2nd century. The largest groups of Early Christian paintings come from the tombs in the Catacombs of Rome, and show the evolution of the depiction of Jesus, a process not complete until the 6th century, since when the conventional appearance of Jesus in art has remained remarkably consistent.

Until the adoption of Christianity by Constantine Christian art derived its style and much of its iconography from popular Roman art, simply from this point chiliad Christian buildings built under regal patronage brought a need for Christian versions of Roman elite and official art, of which mosaics in churches in Rome are the most prominent surviving examples. Christian art was caught up in, simply did not originate, the shift in way from the classical tradition inherited from Ancient Greek fine art to a less realist and otherworldly hieratic style, the get-go of gothic art.

Middle Ages [edit]

Much of the art surviving from Europe after the autumn of the Western Roman Empire is Christian art, although this in large office because the continuity of church ownership has preserved church building art better than secular works. While the Western Roman Empire's political construction substantially collapsed after the fall of Rome, its religious hierarchy, what is today the mod-day Roman Catholic Church deputed and funded production of religious art imagery.

The Orthodox Church of Constantinople, which enjoyed greater stability inside the surviving Eastern Empire was key in commissioning imagery there and glorifying Christianity. As a stable Western European guild emerged during the Center Ages, the Cosmic Church led the manner in terms of art, using its resources to commission paintings and sculptures.

During the development of Christian art in the Byzantine Empire (see Byzantine fine art), a more than abstruse artful replaced the naturalism previously established in Hellenistic art. This new style was hieratic, significant its primary purpose was to convey religious significant rather than accurately render objects and people. Realistic perspective, proportions, calorie-free and colour were ignored in favour of geometric simplification of forms, reverse perspective and standardized conventions to portray individuals and events. The controversy over the use of graven images, the interpretation of the Second Commandment, and the crunch of Byzantine Iconoclasm led to a standardization of religious imagery within the Eastern Orthodoxy.

Renaissance and early on modernistic menses [edit]

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 brought an terminate to the highest quality Byzantine art, produced in the Regal workshops at that place. Orthodox art, known as icons regardless of the medium, has otherwise connected with relatively little modify in subject and style up to the nowadays day, with Russian federation gradually becoming the leading centre of production.

In the West, the Renaissance saw an increase in monumental secular works, although Christian art continued to be commissioned in peachy quantities past churches, clergy and by the aristocracy. The Reformation had a huge impact on Christian fine art; Martin Luther in Germany allowed and encouraged the display of a more limited range of religious imagery in churches, seeing the Evangelical Lutheran Church building as a continuation of the "ancient, apostolic church".[two] Lutheran altarpieces like the 1565 Last Supper by the younger Cranach were produced in Deutschland, especially by Luther's friend Lucas Cranach, to supercede Cosmic ones, often containing portraits of leading reformers as the apostles or other protagonists, but retaining the traditional depiction of Jesus. As such, "Lutheran worship became a circuitous ritual choreography set in a richly furnished church interior."[3] Lutherans proudly employed the use of the crucifix as it highlighted their high view of the Theology of the Cross.[2] [4] Thus, for Lutherans, "the Reformation renewed rather than removed the religious image."[5] On the other manus, Christians from a Reformed background were generally iconoclastic, destroying existing religious imagery and usually simply creating more in the form of volume illustrations.[2]

Artists were commissioned to produce more secular genres like portraits, landscape paintings and because of the revival of Neoplatonism, subjects from classical mythology. In Catholic countries, production of religious art continued, and increased during the Counter-Reformation, but Catholic art was brought nether much tighter control by the church hierarchy than had been the case earlier. From the 18th century the number of religious works produced past leading artists declined sharply, though of import commissions were still placed, and some artists continued to produce large bodies of religious fine art on their own initiative.

Modern period [edit]

As a secular, non-sectarian, universal notion of art arose in 19th-century Western Europe, ancient and Medieval Christian art began to be collected for art appreciation rather than worship, while contemporary Christian art was considered marginal. Occasionally, secular artists treated Christian themes (Bouguereau, Manet) — but only rarely was a Christian artist included in the historical catechism (such as Rouault or Stanley Spencer). Even so many mod artists such as Eric Gill, Marc Chagall, Henri Matisse, Jacob Epstein, Elisabeth Frink and Graham Sutherland have produced well-known works of art for churches.[6] Salvador Dalí is an artist who had too produced notable and pop artworks with Christian themes.[7] Gimmicky artists such equally Makoto Fujimura have had significant influence both in sacred and secular arts. Other notable artists include Larry D. Alexander and John August Swanson. Some writers, such equally Gregory Wolfe, see this equally part of a rebirth of Christian humanism.[8]

Popular devotional art [edit]

Since the advent of printing, the auction of reproductions of pious works has been a major chemical element of popular Christian culture. In the 19th century, this included genre painters such as Mihály Munkácsy. The invention of colour lithography led to broad apportionment of holy cards. In the mod era, companies specializing in mod commercial Christian artists such as Thomas Blackshear and Thomas Kinkade, although widely regarded in the fine art earth as kitsch,[ix] accept been very successful.

Subjects [edit]

Subjects oftentimes seen in Christian art include the following. See Life of Christ and Life of the Virgin for fuller lists of narrative scenes included in cycles:

Motifs [edit]

The Virgin Mary is shown spinning and weaving, actualization in artworks with a loom or knitting needles, weaving material over her womb, or knitting for her son. The imagery, much of it German, places the sacred narratives in the domestic realm.[x] She is shown weaving in paintings of The Annunciation, or spinning. Although spinning was less common an case is plant in some convents where nuns would spin silk, presumably to create a link between the convent community of women and the epitome of the Mary.[11]

Come across also [edit]

A rare sample of medieval Orthodox sculpture from Russian federation

- Andachtsbilder

- Archangel Michael in Christian art

- Cosmic Church art

- Christian icons

- Christian music

- Christian poetry

- Christian symbolism

- Saint symbolism

- Crucifixion in the arts

- God the Male parent in Western art

- Holy Spirit in Christian art

- Trinity in Christian art

- Iconography

- Illuminated manuscript

- Islamic influences on Christian fine art

- Listing of Cosmic artists

- Resurrection of Jesus in Christian art

- Sacri Monti of Piedmont and Lombardy

- Theological aesthetics

Notes [edit]

- ^ "The Religious Prohibition Against Images". The David Collection . Retrieved August seven, 2021.

- ^ a b c Lamport, Marker A. (31 August 2017). Encyclopedia of Martin Luther and the Reformation. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 138. ISBN9781442271593.

Lutherans continued to worship in pre-Reformation churches, more often than not with few alterations to the interior. It has even been suggested that in Federal republic of germany to this day one finds more aboriginal Marian altarpieces in Lutheran than in Cosmic churches. Thus in Germany and in Scandinavia many pieces of medieval art and architecture survived. Joseph Leo Koerner has noted that Lutherans, seeing themselves in the tradition of the ancient, apostolic church building, sought to defend also as reform the employ of images. "An empty, white-washed church proclaimed a wholly spiritualized cult, at odds with Luther's doctrine of Christ's real presence in the sacraments" (Koerner 2004, 58). In fact, in the 16th century some of the strongest opposition to destruction of images came non from Catholics but from Lutherans confronting Calvinists: "Yous blackness Calvinist, you give permission to blast our pictures and hack our crosses; we are going to nail you and your Calvinist priests in render" (Koerner 2004, 58). Works of art connected to be displayed in Lutheran churches, often including an imposing large crucifix in the sanctuary, a clear reference to Luther'southward theologia crucis. ... In contrast, Reformed (Calvinist) churches are strikingly dissimilar. Usually unadorned and somewhat defective in aesthetic appeal, pictures, sculptures, and ornate altar-pieces are largely absent-minded; there are few or no candles, and crucifixes or crosses are also generally absent-minded.

- ^ Spicer, Andrew (five December 2016). Lutheran Churches in Early on Modern Europe. Taylor & Francis. p. 237. ISBN9781351921169.

As it adult in due north-eastern Germany, Lutheran worship became a complex ritual choreography set in a richly furnished church interior. This much is evident from the background of an epitaph pained in 1615 by Martin Schulz, destined for the Nikolaikirche in Berlin (see Figure five.5.).

- ^ Marquardt, Janet T.; Jordan, Alyce A. (fourteen January 2009). Medieval Art and Compages after the Centre Ages. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 71. ISBN9781443803984.

In fact, Lutherans often justified their continued use of medieval crucifixes with the aforementioned arguments employed since the Middle Ages, equally is evident from the case of the altar of the Holy Cross in the Cistercian church of Doberan.

- ^ Dixon, C. Scott (9 March 2012). Contesting the Reformation. John Wiley & Sons. p. 146. ISBN9781118272305.

According to Koerner, who dwells on Lutheran art, the Reformation renewed rather than removed the religious image.

- ^ Beth Williamson, Christian Art: A Very Curt Introduction, Oxford Academy Printing (2004), page 110.

- ^ "Dalí and Religion" (PDF). National Gallery of Victoria, Australia.

- ^ Wolfe, Gregory (2011). Beauty Will Save the World: Recovering the Human in an Ideological Age. Intercollegiate Studies Found. p. 278. ISBN978-1-933859-88-0.

- ^ Cynthia A. Freeland, But Is It Art?: An Introduction to Art Theory, Oxford University Press (2001), page 95

- ^ Rudy, Kathryn M. (2007). Weaving, Veiling and Dressing: Textiles and their Metaphors in the Late Middle Ages. Brepols. p. 3.

- ^ Twomey, Lesley K. (2007). The Textile of Marian Devotion in Isabel de Villena'due south Vita Christi. Brepols. p. 61.

References [edit]

- Grabar, André (1968). Christian iconography, a report of its origins . Princeton University Press. ISBN0-691-01830-8.

- Régamey, Pie-Raymond (1952). Fine art sacré au XXe siècle? Éditions du Cerf.

- Jean Soldini, Storia, memoria, arte sacra tra passato e futuro, in Sacre Arti, by Flaminio Gualdoni (editor), Tristan Tzara, Due south. Yanagi, Titus Burckhardt, Bologna, FMR, 2008, pp. 166–233.

Further reading [edit]

- Evans, Helen C.; Wixom, William D. (1997). The glory of Byzantium: fine art and culture of the Middle Byzantine era, A.D. 843-1261 . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN9780810965072.

External links [edit]

- Princeton'southward Index of Medieval Fine art

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_art

0 Response to "Medieval Art Showing Jesus Classical Art Taht Is More Perfect Than Real Life"

Post a Comment